Home / Firearms & Gun Parts / The STEN Gun

The STEN Gun

William Lawson

The British STEN Gun was born from desperation. Early June 1940 had seen the British Expeditionary Force ignominiously kicked off the European Continent. A herculean rescue effort pulled 340,000 men from the Dunkirk beaches, but all their equipment had to be left behind for the victorious Germans. France was two weeks away from total capitulation and it didn’t take a genius to figure out that Adolf Hitler would quickly turn his focus to the island nation across the English Channel.

In a June 4 speech before Parliament, Winston Churchill declared “We will never surrender!” His nation needed to hear that, but the truth was they had little with which to back it up. The threat of a German invasion was very real at the time. A seaborne invasion ultimately proved impractical, but that fact wasn’t evident just then.

The British needed arms for those rescued soldiers and they needed them yesterday. The STEN Gun helped to fill that need. But what exactly is a STEN Gun?

What is a STEN gun?

The STEN is a British submachine gun based on the earlier Lanchester submachine gun, which was, in turn, a direct copy of the German MP28. The STEN was specifically designed for fast and cheap mass production with stamped sheet steel components welded together. Only the bolt and barrel were of high-grade machined steel.

The acronym “STEN” stands for the first letters of the last names of the designers, Major Reginald V. Shepherd, and Mr. Harold Turpin. The “EN” came from Enfield, the famed firearms manufacturer where the weapon was developed.

Chambered in 9mm Luger and fired from the open bolt, it worked well enough, could be produced at a prodigious rate, and was affordable. The 9mm chambering was copied from captured German MP28 and MP38 submachine guns.

How a STEN Gun Works

The STEN’s simplicity was key to its mass production appeal. It fired from the open bolt, using a fixed firing pin. The blowback cycled the action. The gun had no mechanical safety, with the charging handle rotating into a slot to safe the gun. The sights were a simple rear aperture and a large triangular front post.

The STEN’s most recognizable feature is the side-mounted magazine well. It made the gun easy to fire from the prone, but it was difficult to grasp properly with the support hand. Soldiers often grasped the mag well from the top, though they had to be careful about putting pressure on the mag.

The mags were not especially reliable to start with since they were double-stack single feed models, which caused feeding issues. The mags held 32 rounds, but the feeding problems could be mitigated by downloading them to 30.

Exerting pressure on the mag while in operation could easily cause a failure to feed. Soldiers were taught to grip the gun under the heat shield, like a regular rifle, with the mag resting on top of their arms. Some did that but many continued to grip the mag well from the top.

The poorly designed magazines contributed significantly to the STEN gun’s reputation for jamming. Even more alarming was the propensity of the open bolt guns to fire if dropped and sometimes keep firing until the mag was empty.

Some British soldiers supposedly chucked cocked and loaded STENs into roomfuls of enemy soldiers, knowing they would run themselves in circles until it was empty. It sounds like Hollywood stuff, but the stories are out there.

The most credible account that I saw was from a Canadian officer in Korea in 1953 who tells the story of one of his men dropping his STEN and he and others trying to avoid it:

At first, we did some shy polka steps to avoid getting hit, but as the rotation speed increased so did our dance. With about 10 rounds to go the muzzle of the weapon started flipping up, as if looking for a larger target. It was then that the first primitive steps of what would later become known as break-dancing came into being… (Quote: Legion magazine, April 1994)

You can decide for yourself, but I tend to believe it based on seeing similar stories in many different places.

The History of the STEN

The British Army entered World War II without a domestic submachine gun. The short campaign on the Continent showed the need for such a weapon, especially after seeing the German MP38 in action. The Brits had some American Thompsons, but not nearly enough.

Desperately Seeking a Submachine Gun

Thanks to the isolationist sentiments of the United States, Congress stipulated that any war material sold to belligerents had to be paid for in hard currency, meaning actual gold. Thompsons were expensive to produce. In 1940, one Thompson cost about $200 to make. That’s over $4,400 in today’s money. For a nation that needed lots of everything, spending their limited gold reserves on submachine guns was more than impractical.

A couple of German submachine gun copies were tried after acquiring some examples from Ethiopia. The British produced fifty thousand Lanchester submachine guns, but they were heavy, complicated, and expensive. Most ended up with the Royal Navy and many served into the 1970s as an anti-boarding weapon. But the Lanchester was not the answer.

Britain needed a cheap, easily produced gun. The STEN fit the bill.

Different Versions of the STEN

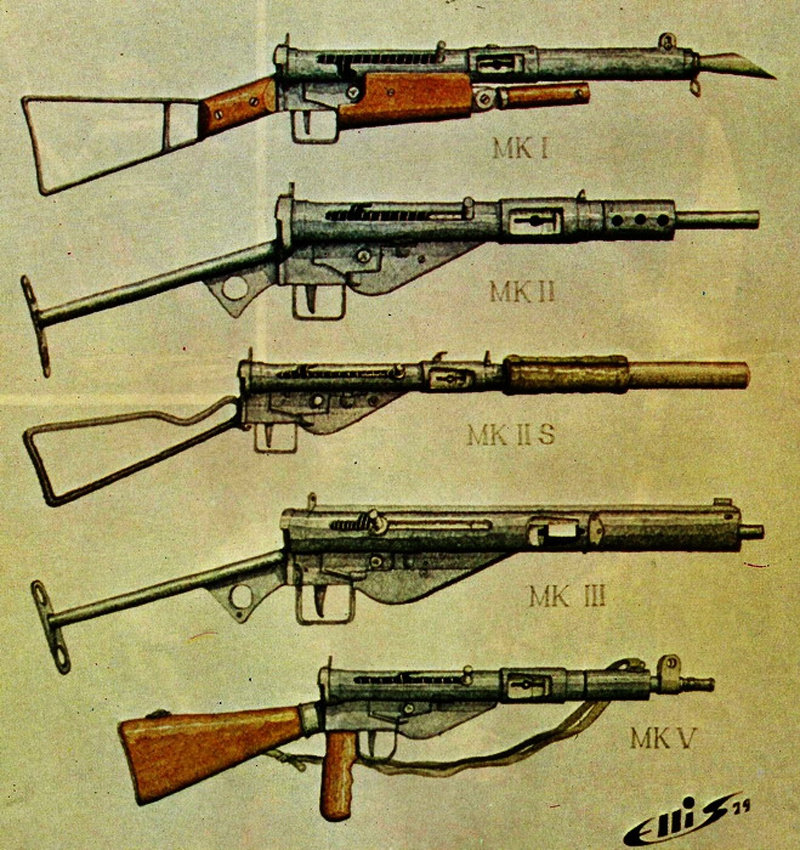

Eventually, the STEN series yielded five official versions, Mk I through Mk VI. The Mk IV was a proposed airborne version that was never adopted, so there was never an actual Mk IV produced. There was also the Mk I* (read as “Mark I Star”) which was a simplified Mk I and doesn’t count as its own version. The Mk I* served as the basis for the Mk II, which was the most produced version by far and is considered the “classic” STEN gun.

The STEN underwent a series of evolutions that, somewhat ironically, seemed to go almost full circle in terms of the gun’s features.

The Mk I had a sturdy skeletal stock, wood handguard and “pistol grip,” barrel-length heat shield, flash suppressor, and a folding vertical foregrip. The side mag well could be rotated down for storage and transport. The rotating mag well also served as a dust cover for the ejection port. A large barrel nut allowed the barrel to be easily removed for cleaning or storage.

The Mk I* lost the wood, the foregrip, and the flash suppressor, creating the eventual Mk II’s bare-bones look.

As noted earlier, the key thing to remember with the STEN’s development is that the British needed lots of them at the cheapest price in the shortest time possible. There was little thought given to ergonomics other than basic functionality and aesthetics were not considered at all. Having a Nazi knife at the national throat will do that.

1943 saw the introduction of the Mk III, which simplified the Mk II by eliminating the removable barrel, making the gun a monolithic sheet metal tube. Mk III parts, however, were not always interchangeable with other STEN models and the one-piece gun made maintenance difficult.

Even so, 876,000 Mk IIIs were made. To put that in perspective, the United States only manufactured 655,390 M3 “Grease Guns” of all configurations, ever. The British Army was literally awash in STEN guns by the end of the war. Even the Germans used captured STENs. Their version of the Mk II was the MP 3008, and the Mk III was called the MP 750(e).

The STEN Mk V came along in 1944, by which time the threat against Britain had eased considerably and the Germans were on the defensive. The Mk V reflected those changed conditions in that it was built more with quality and ergonomics in mind, though it was still a cheap submachine gun.

The new gun had a proper wooden stock and pistol grip. Some had a wooden vertical foregrip, hearkening back to the Mk I just a bit. The rear aperture sight was retained but instead of the crude triangle front sight, the Mk V sported a Lee Enfield Rifle front sight. The Mk V also had a lug for a Lee Enfield bayonet.

Britain built 527,000 Mk Vs between February 1944 and the end of the war in 1945.

In my research I saw several examples of what appeared to be STENs with parts from other models, mostly the Mk II and especially the stocks. I can’t say why that is, other than the number of models and the need to slap them together quickly may have led to some production overlap or maybe they were modified later with available parts.

The STEN MK II

The STEN Mk II deserves special mention, being the most familiar model. The British adopted the Mk I in March of 1941 and about 300,000 were made. 200,000 of those were Mk I*s. The STEN’s development was so fast that five months later, in August, the even simpler Mk II entered production.

Keep in mind that Britain was still fighting Hitler alone until June 22nd of that year, when the Nazi warlord stabbed his Russian allies in the back with Operation Barbarossa. Even then, the best estimates predicted a Soviet collapse by fall. The British kept producing weapons as fast as they could.

And turn them out they did. A complete STEN Mk II required five and a half man hours to make at the height of its production run. Factories could build 500 units in a single shift.

They were cost effective too. Fifteen Mk II STENs cost the same as one American Thompson at the 1940 price. Britain cranked out over two million STEN Mk IIs during the war. Even accounting for its two-year head start, STEN production dwarfed that of the Grease Gun.

The Special Ops STEN Mk II (S)

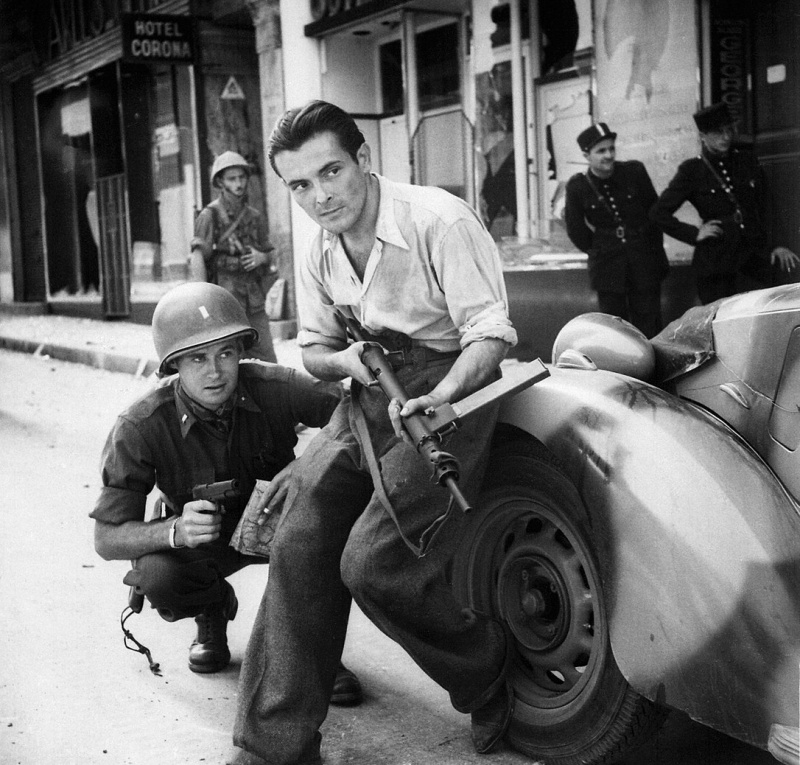

A suppressed version of the Mk II was developed for special operations, most notably the Special Operations Executive (SOE). The SOE operated in occupied Europe assisting resistance fighters in every nation.

The STEN Mk II (S) was intended not only for SOE operatives but was dropped to those freedom fighters by the hundreds, and maybe thousands. The “S” stands for “Special Purpose,” not “suppressed” or “silenced.”

The suppressor’s baffle system wasn’t especially durable and the suppressed STENs were meant to be fired in single shots or, at most, small bursts. Even one magazine on fully automatic could ruin the baffles, defeating the suppressor’s purpose.

Since the SOE intended the suppressed guns for missions like sentry elimination or assassinations, as opposed to hard front-line combat, this wasn’t usually a problem. Some were produced in semi-auto only. The guns came with a canvas handguard, with horsehair or asbestos string, on the suppressor.

The reduced energy from the cartridge meant the action needed attention as well. The danger was that the gun could short stroke and jam or, even worse, cycle just enough to pick up a round without engaging the sear, resulting in a runaway gun. Engineers solved this problem by slicing off some of the bolt, thus reducing its weight from 600 grams to about 493. A coil was also taken from the recoil spring.

Interestingly, the factory armorers seem to have tailored each spring to its particular bolt and suppressor. These were not precision parts by any stretch. So, each spring’s length may vary a bit, making the suppressor, bolt, and recoil spring a set that is not necessarily interchangeable with other guns.

Another interesting thing about suppressed STEN Guns is that, despite the mostly standardized Mk II (S), the SOE and its operatives modified numerous guns for suppression in the field. If you run across a suppressed STEN that doesn’t match the description above, that doesn’t mean it’s not authentic.

Very late in the war, a suppressed version of the Mk V was implemented but it saw little action in World War II. This was the Mk VI. It used the same suppressor system as the Mk II, just with Mk VI parts everywhere else.

Modern Suppressed STEN Guns

There are also modern suppressed STENs out there. The sheer number of guns, and their adaptability, make it easy if you know what you’re doing.

The guys at SilencerCo have a Mk II that they’ve threaded at 1/2×28 for their Omega 9K and short-configured Omega 36M suppressors. Their setup is likely far more durable and reliable than the World War II versions. So, if you’re looking to suppress your STEN, it’s possible. Go for it.

How much is a STEN gun worth today?

You can theoretically purchase a real STEN Gun even today. I say “theoretically” because some hoop jumping is required. First, you’ll have to find one for sale. Good luck with that. I found one dead listing on an online auction site, and two that Rock Island Auctions put on the block in 2011 and 2023, respectively. Both were Mk II STENs with the wire stock.

Then, you’ll need an ample bank account. The 2011 gun sold for $5,750, while the 2023 sale brought $9,988. For some perspective, these guns cost approximately $13 each in 1942, which translates to $255 in 2024 money. STENs are not top-quality firearms. But, of course, you’re paying for the historical value and the fact that they are fully automatic weapons.

Which brings us to the third hoop. A Class III NFA weapon like the STEN requires ATF permission and a $200 tax stamp. But if you’re paying 10 grand for a gun, what’s another 200 bucks? So, if you simply must have that STEN, knock yourself out.

The Right Gun at the Right Time

The STEN Gun, while not perfect by any means, was good where it had to be. Despite being officially replaced by the Sterling in 1951, it stayed in British Service, in one form or another, until 1971. After all, Britain built some 4.6 million STEN guns.

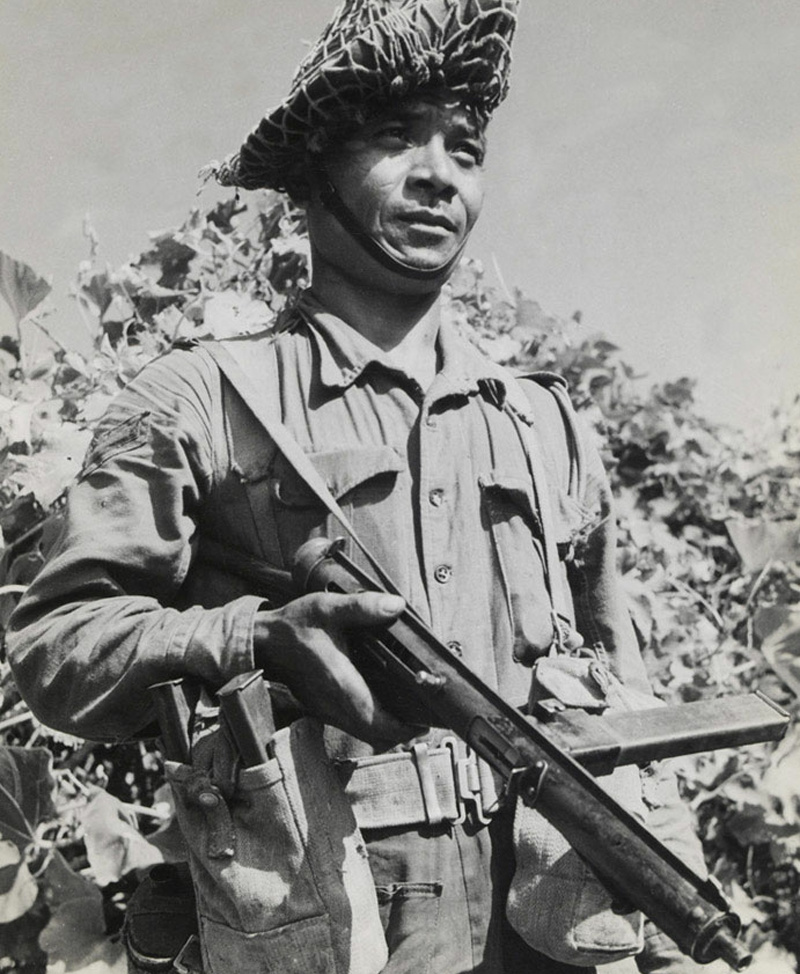

The STEN’s cheap but ruggedly simple construction meant that it was easily produced and attractive outside Britain. It was copied by the Germans during the war and afterward by France, Norway, Denmark, Poland, Austria, Argentina, and Belgium. Many resistance units, most notably the Norwegians, produced their own STENs during the war. STEN Guns saw hard post-World War II service in Korea, Vietnam, and the India-Pakistan Wars.

Despite being a desperate wartime expedient, the STEN Gun’s sound design served Great Britain, and the Allied cause, admirably. The STEN deserves its place among the great infantry weapons of World War II and the Twentieth Century.