The National Firearms Act (NFA) of 1934

David Higginbotham

Gun law can get complicated. Yet there are some 90-year-old foundational rules that govern most of what we do today that are worth understanding. We are going to unpack some of these today to help you better understand the complexity — and it all begins with the Firearms Act of 1934.

What is the National Firearms Act of 1934?

The National Firearms Act of 1934 was an epic bit of legislation in firearm regulation. It made ownership of silencers, short barreled rifles, and short barreled shotguns (and much more) far more complicated.

Before 1934, a rifle might have had a short barrel, but it wasn’t a “short-barreled rifle” (SBR). The NFA redefined certain terms and mandated owners to pay a $200 tax for registration — a substantial sum, equivalent to more that $4,600 adjusted for inflation today.

Why did we need a National Firearms Act in 1934? The vast majority of gun owners in the 1930s used their firearms in the same fashion we do today: lawfully and legally. In the wake of the great depression, crime was rampant. Mass media was coming into its own, which fueled hysteria. And the squeaky wheel of gun crime attracts the grease of new and restrictive laws.

Machine guns, sawed-off guns that mobsters were allegedly hiding beneath their trench coats, invisible assassins with their completely inaudible rifles, and a host of other gun-type-things that looked like innocent everyday objects struck fear into the populace.

To quell the madness, politicians from both parties, and even the NRA, supported The National Firearms Act of 1934 (NFA)

Where are full auto firearms illegal in the United States?

Possession and/or ownership of select fire and automatic guns is illegal in these states:

- California

- Colorado

- Delaware

- Hawaii

- Illinois

- Iowa

- Louisiana

- Massachusetts

- Minnesota

- New Jersey

- New York

- Rhode Island

- Wisconsin

In addition, some states crack down on the manufacture of these devices. You can’t make or build automatic guns in California, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, or Rhode Island. And you can’t sell them there, either, which would seem like a logical conclusion, if it weren’t for New York, where sales remain legal.

The NFA set the federal standard. It placed the matter of taxation squarely under the control of the Treasury. Yet enforcement of these regulations fell (and falls) to a variety of agencies, including the BAFTE.

All states could use the standard set by the NFA itself, yet some have enacted further restrictions. This is where the layered questions of legality begin to overlap and — as is always the case in such matters — when in doubt (or any old time, really) it is best to seek professional legal counsel.

Why the NRA backed the FFA and the NFA

As the title of this section suggests, there is some controversy surrounding the National Rifle Association’s support of the NFA. The NRA came out on the side of government, throwing its collective weight behind the NFA, an act that helped ensure its passage. Why?

If you’re inclined to give them the benefit of the doubt, the NRA’s support seems like an act of compromise. Early considerations of exactly which guns would be regulated by the NFA included handguns and pistols. If the extremists had their ways, we’d have to pay the $200 tax stamp for those, too. And it is safe to say that the NRA lobbied against such actions.

At what cost? There were concessions. Remember that there is not one single identifying feature that unites gun owners in this country. Many are hunters that don’t have a lot in common with those that carry concealed for self-defense.

Could it be that the leadership of the NRA felt compelled to give up short-barreled guns and suppressors in order to keep ownership of long-guns and handguns off the NFA lists?

And this is the 1930s. How much were they really giving up? Consider what silencers must have looked like in the era before aluminum, titanium — before effective stainless alloys. If the passage of the NFA had been deemed an inevitability, the NRA might have shown support in order to keep it from becoming even more draconian.

Again, in 1938, the NRA threw its weight behind another measure that continues to stir controversy. The Federal Firearms Act of 1938 is most widely remembered because this is the act that created licensure for firearms dealers. And the NRA assumed that licensure and tighter control on buyers and sellers would cut down on gun crime — something that has always made law-abiding gun owners look bad through guilt by association.

Those who would never support any restriction of inalienable rights find fault with the NRA’s support for both the NFA and the FFA. There’s reason, though, to study this support and understand it fully, even if the position isn’t one you’d ever endorse.

What is an NFA Weapon?

Let’s consider the term “weapon” as it is employed in legislative contexts, particularly within the framework of the NFA. A “weapon” is an object designed or used for inflicting bodily harm or physical damage. A weapon can also be anything used as a means of gaining an advantage while defending oneself in a conflict or contest. This dual nature of the term adds a layer of complexity when discussing firearms, which are often categorized by most people simply as tools for sport or hunting.

Legislatively, labeling all firearms as “weapons” subtly affects public perception and policy. It suggests a potential desire to limit one’s ability to defend oneself.

Despite the word’s negative associations with aggression and violence, “weapon” remains a critical term in the NFA, encompassing the regulated types of firearms and influencing key discussions about rights, regulations, and their societal impact.

What are the weapons called out by the NFA?

Machine Guns

A machine gun is a device that, with one single pull of the trigger, fires multiple rimfire or centerfire cartridges in sequence.

The machine gun classification has proven murky of late. More and more devices like bump-stocks and assisted reset triggers are being lumped in to the “machine gun” designation by those wanting to place restrictions on the devices.

Short Barreled Rifles

The original ruling was that a centerfire rifle had to have 18 inches of barrel in order to avoid the SBR designation. Rimfires were allowed to be 16 inches. After a few years, all rifles were dropped back to 16 inches, which explains why so many carbines have barrels 16.5 inches in length.

Short Barreled Shotguns

Shotguns, it was determined, needed 18 inches of barrel. Anything under that would be considered a short barreled shotgun. This designation is easy enough, and still in play today, except for a big hitch that comes in the “firearm” designation.

There are some smooth-bore guns that fire rounds more commonly associated with a shotgun or short barreled shotgun. If these leave the manufacturer with some kind of pistol grip, and a barrel that is at least 14 inches long and an overall length of at least 26 inches, then this is neither a shotgun or a short barreled shotgun. This is a “firearm” by definition. Not a shotgun. Not a short barreled shotgun.

Silencers

A silencer (aka suppressor, or—as the NFA describes it—a “muffler”) is a device designed to limit the damaging noise produced by a gun’s report.

Why the demonization of silencers? There has, since the first practical demonstrations of silencers, existed an irrational fear of silent gunshots. While educational efforts of organizations like the American Suppressor Association have done much to counteract the hyperbole, the mainstream media continues to exaggerate the dangers and stoke the fears.

Any Other Weapons

Just about anything that doesn’t fit the traditional designation of common firearm types, or the new classes created by the NFA of 1934.

- Pen guns.

- Disguised guns.

- Ballistic knives.

- Cane guns.

If it isn’t really a “gun” in the traditional sense, but still shoots like a gun (but not like a muzzleloader or air gun), than it could well be an AOW.

And, as if the “firearm” classification we noted earlier wasn’t already confusing enough, some similar guns (devices that fire shot shells) with barrels under the 14 inch designation, or total overall lengths under 26 inches can be classed as AOWs. I’ve always thought the AOW classification smacked of legislative desperation.

But Wait, There's More!

These sweeping classes created new types of guns, but some actual gun parts ended up getting thrown under the legislative bus, too. Vertical grips on pistols are one. As the ruling is often interpreted, a pistol is a gun meant to be fired one-handed.

As if all of this wasn’t enough, the NFA rounded up another class of verboten items they labeled as “destructive devices.” Untangling that mess is a topic for another essay. Let’s just say destructive devices put the E in BATFE.

Buying and Owning NFA Weapons

Let’s assume you live in an area where owning NFA firearms is legal. Ownership comes with some obligations. Knowing them is your responsibility.

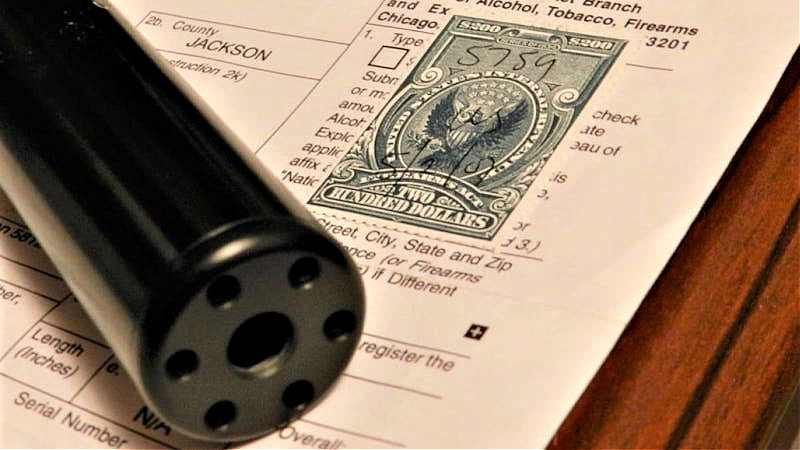

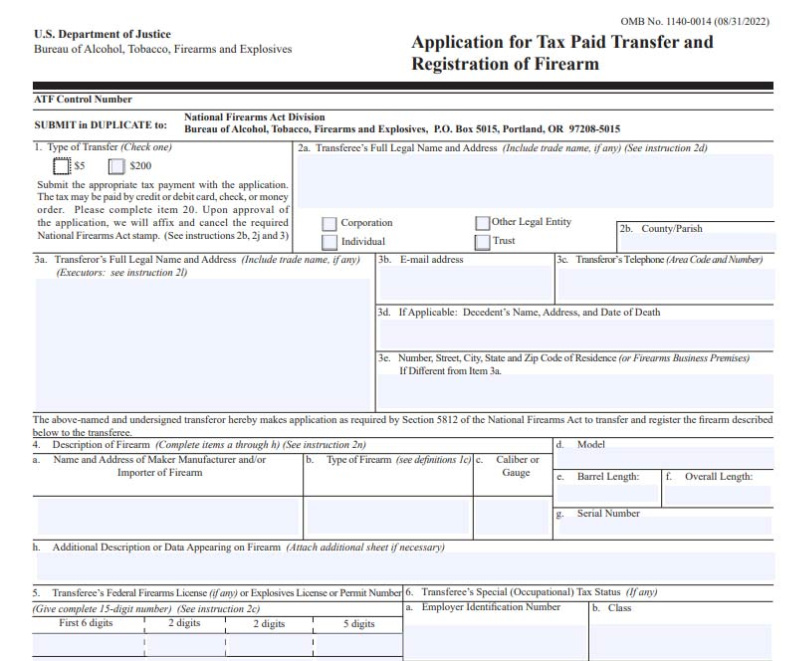

While it often seems like buying them is cumbersome, it isn’t complicated. There’s an application to be filled out and submitted to the BATFE. Along with this, you need an old-school fingerprint card or a digital set of fingerprints. You have to provide notice of your application to your Chief Law Enforcement Officer (CLEO). And you need to provide Uncle Sam $200 for the tax stamp.

The process used to be entirely paper-based, but is now available online as the eForm 4. Having done this several times myself (both as an individual and as part of a trust), I can say that it is more complicated than filling out the old school Form 4473, but completely worth it.

How many NFA items can one purchase at a time?

Assuming you remain in good standing with the local authorities and with the BATFE, there’s no set limit on how many NFA items you can procure. You will have to apply for them individually, as each requires a separate tax stamp.

It bears mentioning that there are some obligations I’d encourage you to consider. While NFA items can be bought and sold, many of these end up being passed down to spouses and children who may be unclear about the legal ramifications of possession of these guns and devices. I’m a big advocate for setting up a trust and keeping everyone both informed and aware about what happens after the inevitable occurs.

Is the NFA Unconstitutional?

From where I’m sitting, just about one mile from the United States District Court for the Western District of Arkansas, where the first major challenge to the constitutionality of the NFA began, I will profess that I believe the NFA to be an infringement on my rights. As a working professional in the industry, however, I abide by its strictures. To the letter.

But let’s go way back to 1938. Two alleged ne’er-do-wells toted a sawed off shotgun across the Oklahoma line in to Arkansas, and were arrested and tried for the act.

The defendants argued that the NFA violation was unconstitutional. Many believe the Western District Court sustained the argument and sided with the defendants only to tee-up a sweeping ruling from the Supreme Court (who immediately took up the case on appeal). That decision came in the 1939 United States v. Miller decision.

Why this hasn’t been made into a movie, I don’t know. Miller, one of the defendants, was an alleged bank robber who had agreed to be testify against his former gang. The district court acquitted him, knowing he’d have to run for his life (from his former gang members). This meant there was no way he’d turn up in DC for the Supreme Court hearings.

He didn’t show. Before the ruling was announced, he’d been murdered.

But the Supreme Court still delivered their ruling in the case. Two major points were established. The first is that the NFA generates revenue for the Department of the Treasury. As such, the ruling is used to quell any states-rites arguments.

The second point had to do with the idea that the Second Amendment only applies to guns that may have a military use. This had been the crux of the argument used to acquit Miller—since the Second Amendment clearly references “a well regulated militia”, there could be no limitation on guns that might be used by a militia. Did a short barreled shotgun have a military purpose? This question was at the heart of the case.

If you have any interest at all in understanding the machinations of the judicial branch as it relates to firearms law and opinions, United States v. Miller is required reading. It doesn’t diassapoint.

Is it time to repeal the NFA?

Clearly.

I’ll speak to one point here, while I can still hear the click-clack of the keys on my laptop. Every gun that can be silenced, should be silenced.

As an absolutist when it comes to matters of personal freedom, I’d gladly lead a repeal of the NFA. The reasoning behind the NFA seems flawed. And the legal distinctions on barrel length for rifles and shotguns seem arbitrary.

Silencers, thankfully, have continued to develop. I’d like to silence every gun I have, yet that remains impractical, thanks to the NFA.

We no longer live in 1934. The efficacy of the NFA is dubious. Thankfully, the financial hurdle established in 1934 remains the same, and the processes have become more efficient. With digital fingerprint files, eForm 4, and $200 tax stamps, it is far less burdensome than it could be.