Decibels of a Gunshot and What It Does to Your Hearing

David Higginbotham

I spend more than my fair share of time at firearm industry events. These are always attended by folks like me, who shoot guns for a living. While we may argue about calibers and makes and models, there’s one thing we all have in common: some degree of hearing loss.

Why? Guns are loud.

We are a loud-talking bunch, for sure, when we’re off the range. We have to be. All of us, at one time or another, have been in close proximity to a gunshot (or many) without hearing protection.

The first time I pulled the trigger on a gun without hearing protection was when I was a teen — hunting in Alabama. I had no clue what I was doing and touched off a .30-06. All auditory input stopped and was replaced by a shrill, high-pitched whine that lasted several minutes.

Years later, I was trying to dispatch a rabid raccoon and pulled the trigger on a .357. Instantly, I was reminded of why hearing protection is so crucial. I mark this as a turning point in my hearing loss.

Throw in a few dozen air shows and more concerts than I can count, and it is a miracle that I can hear anything. Tinnitus is a real thing, and a constant for me. The perpetual ringing in my head is something I’ve learned to live with. I have no other choice.

So when I got my first suppressor — a SilencerCo Sparrow — well over a decade ago, my relationship with noise changed dramatically. No exaggeration — silencers change everything.

What is a decibel?

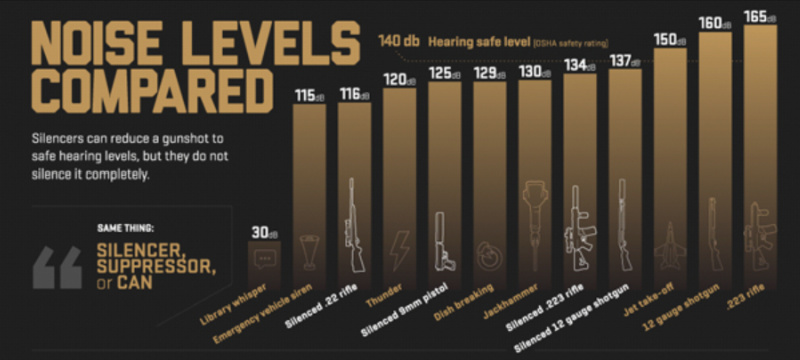

Sound is measured in decibels (dB) on a logarithmic scale, and scientists classify noise in decibel rankings. The higher the number, the louder the sound. Total and complete silence is 0 dB. Sounds 10 times louder than total silence would be 10 dB, and sounds 100 times louder than silence are 20 dB. As you can see, every 10 dB increase is a multiple of 10 times over the previous rating.

The Two Types of Harmful Sound

There are two kinds of damaging sound that most of us encounter regularly: constant noise and impact noise. Cells and membranes inside the cochlea are damaged by loud noises of both types.

Constant Noise

The first is loud sustained noise that may not initially strike you as damaging but will degrade your hearing over longer periods of exposure. Think lawnmowers, chainsaws, concerts, jackhammers, airplanes…

Sustained noise is enough of an issue that OSHA requires employers to implement a hearing conservation program when noise exposure is at or above 85 decibels, averaged over eight working hours. Even if the sustained noise level stays below 140 dB, the point most experts agree that damage to your hearing occurs, prolonged exposure is bad news.

Impact Noise

The other type, impact or impulse noise, is more easy to identify — extremely loud sounds like the crack of a .243. That hypersonic crack that’s followed by the undertones of the powder blast itself will instantly leave you hurting. Prolonged exposure of repeated impact noise damages the cells in the cochlea and this damage is often progressive and irreparable.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Noise standard states, “Exposure to impulsive or impact noise should not exceed 140 dB peak sound pressure level.” This is the point at which a sound becomes painful.

How many decibels is a gunshot?

Providing a simple answer to this question is impossible because the answers vary based on many factors. Almost all gunshots are loud enough that they’re not considered “hearing safe.”

Let’s begin with a common caliber — the standard .22 LR. This round has a small powder load, and that explosive concussion is loud, but not terrible. When fired from most guns, these rounds are fast enough to break the sound barrier, which adds a hypersonic crack over the top end of the concussive boom. This is often measured over 140 dB. Thus, even the humble .22 LR can damage hearing.

The AR-15, in its somewhat generic form, with basic .55 grain ammo, runs in the neighborhood of 160 decibels, or more. A .30-06 can run more than 170 dB.

What factors affect how loud a gun sounds?

The first is, of course, the proximity to the muzzle. A gunshot echoing through a crisp fall morning is louder for the shooter than someone in a deer stand half-a-mile away.

But even at the range, you will notice that guns like the AR-15 are not as loud if you are behind the gun, pulling the trigger, as they are if you are standing off to one side of the muzzle, as I often do when I’m taking photographs for gun reviews.

There are other factors, too. Caliber is the big one. Hypersonic rounds are louder. Magnum rounds are louder than normal options within a given caliber (like .38 Special and .357 Magnum).

What about subsonic ammo?

Sound travels at 1116.43 feet per second. If a round runs under 1,116 fps (usually well under that mark) we call it subsonic.

Why does this matter? Bullets that break the sound barrier have a loud crack. This is part of the sound we want to dampen with suppressors.

Some rounds are naturally subsonic. Heavy .45 ACP rounds, fired from reasonably short barrels, for example, will stay below the hypersonic threshold.

9mm, though, is almost always hypersonic, unless the bullets are intentionally heavy and the power dialed back just enough — and those will be marketed as subsonic.

Is subsonic ammo better?

Subsonic ammo isn’t always better for everything. I wouldn’t hunt large game with it. It all comes down to how many times you will pull the trigger.

9mm, .45 ACP, and even .22 LR are all prime candidates for subsonic ammunition. If you run a whole mag (or case) of subsonic 9mm through a silenced gun, you won’t ever need additional hearing protection.

Subsonic .308 exists, and is fine for the range, but I wouldn’t try to hunt elk with it. The terminal ballistic performance of subsonic ammo won’t compare to faster moving rounds.

That’s why many hunters who hunt suppressed will go out without hearing protection. A silencer like the Scythe Ti on a 20” barrel will strip .308 back to 132 dB. Even 300 WM remains under 140 dB.

My Sparrow, though, with bog-standard .22 LR, registers 112 dB. With subsonic ammo in a bolt-action rifle, it is almost Hollywood quiet. Anytime you can hear the bullet impact down range, even without the ring of a steel target, you know you’re onto something.

Every gun should be suppressed.

Once you get started down this road, you’ll understand why I feel every gun should be suppressed. The benefits to your hearing, alone, make it worth it.

But there’s more. Once you take that bite out of a firearm’s report, you may find you flinch less, too. This will show in repeat accuracy on the range, and greater concentration when hunting.