Home / Silencer & Gun News / The Nagant M1895 Revolver: Way Cooler than You Think

The Nagant M1895 Revolver: Way Cooler than You Think

Home / Silencer & Gun News / The Nagant M1895 Revolver: Way Cooler than You Think

William Lawson

Russian surplus weapons are awesome. They just are. They’re different, they’re rugged, they’re often cool, and, aside from sticky Mosin-Nagant bolts, they just plain work. One thing Russian surplus weapons are not known for, however, is elegance. There are no Lugers or Mauser 98 rifle actions emanating from the Rodina. The Nagant M1895 Revolver, though, is one firearm with an understated elegance that is overlooked.

The Nagant Revolver is not recognized as one of history’s great battlefield weapons.

Nor should it be. The design was almost twenty years old by the time the Great War kicked off in 1914 and it was pressed into service in the Great Patriotic War (that’s World War II to you and me) out of sheer necessity. The unprecedented size and brutality of the war in the East meant the Russians had to pull out everything they had just to survive and building new tanks and aircraft was a lot more urgent than developing service pistols. The 1895 Nagant ended up being produced at the Tula arsenal until 1950.

So, the Nagant pistol served the Russians for 55-odd years. Not bad for what many people consider an afterthought, at best, when it comes to surplus handguns.

But I think the Nagant M1895 deserves a fresh look.

It will never be my favorite pistol, but it has a certain uniqueness that makes it worthy of inclusion in a MILSURP collection, as well as a couple of other features that make it downright cool. One of those features, though unintended by its designers, is that it is one of the few (I say that because there may be something of which I am unaware) revolvers that can be effectively suppressed.

How is this possible?

Well, it requires some explanation, so read on if you’re so inclined. The tests I saw, however, were nothing short of spectacular from a suppression standpoint. They were movie quiet. The smacking of the hammer was louder than the gun’s discharge.

First, however, we need to address the bad press surrounding the Nagant.

Some of it bordering on downright ridicule. I bought into that stuff for a long time, despite the fact that my son, an unapologetic Russophile when it comes to weapons, has staunchly defended the Nagant M1895 against such aspersions for years. The knocks against the gun are:

- It’s ugly (kinda)

- The trigger is Godawful (the DA is heavy, but thereare reasons)

- It’s slow and unwieldy to load and unload (no argument here)

- It’s unreliable

- It’s inaccurate

The round for which it’s chambered, the 7.62x38R Nagant, is anemic and all but useless as a defensive cartridge

Let’s dismiss the first charge.

It is, as they say, what it is. I will note, however, that the odd-looking grip is surprisingly comfortable.

Moving on, the single-action function of the trigger isn't bad at all.

A little heavy, but I’d describe it more like “solid.” There is no creep, and the break is very crisp. The heavy double-action trigger is a negative by-product of the ingenious and elegant cartridge design and cylinder function. More on that later.

As for loading and unloading...

The thing is, if you approach the Nagant M1895 as a single-action revolver, and there was an early single-action version, its functionality takes on a new light. Mechanically, it’s hardly more difficult to load or unload than a Ruger Blackhawk. The only real difference is that the Nagant’s push rod has to be rotated over to do its job. In 1895, that wasn’t so bad.

The swing-out cylinder was still very new and unproven technology and some service pistols of the day required the user to carry around a wooden dowel to punch out the used brass. The complaints about the Nagant’s operation are largely misguided because they take the pistol out of its chronological context. Yes, it was obsolete by the time it saw combat in World War I, but not so its service in the bloody Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. It was nothing special, but it was representative of a modern service pistol of the time.

So, what about the charges of unreliability, inaccuracy, and weak chambering?

Again, the context is wrong. In terms of size, the 7.62x38R Nagant is, admittedly, a small-caliber round. Keep in mind, however, that standard European defensive rounds of the day were also small. The 6.5mm and 7.65mm were common chamberings for military and police pistols and would be for decades to come. I have an Italian Police Beretta chambered in 7.65mm, which Americans know as .32 ACP. It was built in the 1980s.

Okay then, why is the Nagant round considered to be so weak?

Before addressing that point, we have to look at the understated elegance and uniqueness I mentioned earlier. Anyone possessing a familiarity with revolvers knows about “cylinder gap.” Cylinder gap refers to the gap between the cylinder and the barrel and the escape of energy caused by that gap. Essentially, part of the energy produced by the firing of the cartridge is expended laterally through the gap, thus reducing the muzzle energy of the round and producing a flash. That’s why shooting a revolver at night can ruin your night vision. Many people who don’t like revolvers cite the cylinder gap, which they say is a design flaw, as part of their reasoning. The vast majority of revolver designs accept this perceived flaw as part of doing business. That’s just how revolvers work.

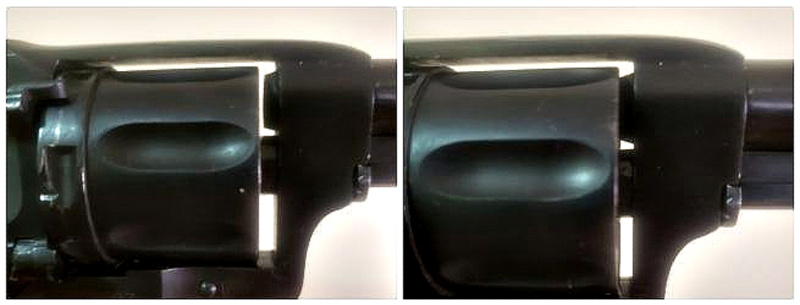

A notable exception to those designers was a Belgian gunsmith named Leon Nagant. Together with his brother Emil, he came up with a simple, yet elegant, fix for the problem of cylinder gap. As part of the cocking mechanism, as the hammer comes back, it moves the cylinder forward to create, along with the cartridge, a seal that prevents the gas and energy from escaping out the sides. The noticeably long firing pin is necessary to reach the primer as the cylinder moves forward.

The cartridge helps the sealing process because of its unusual design. At first glance, it looks kind of like a wadcutter, contributing to the perception of weakness. The brass is tapered up around the cone of the bullet and extends just past the nose. Russian military ammo featured a long consistent tapering while most commercial rounds feature a straight brass case that is crimped just beyond the bullet nose.

Either way, when the cylinder moves forward as the hammer pulls back, the cartridge case enters the barrel, completing the seal. Therefore, all the energy and gas are focused forward through the barrel and out the muzzle. The change gives the round an estimated 50 to 70 FPS in extra velocity, which translates to more energy at the muzzle and on the target.

The sources I found rate the Nagant’s performance, with 108-grain military ammo, at 900to 1,100 FPS. Not the most consistent performance, but I looked at several tests, and with military ammo, the Nagant outperformed the .32 ACP and was comparable to the.380 ACP. One test, with surplus ammo testing in the 950 FPS range, went through four layers of denim and produced a 20-inch penetration of ten percent ballistic gel at a range of about three yards. The wound cavity was well-defined and fairly large.

So, again, why does the cartridge, and the gun for that matter, have a reputation for weakness and unreliability? That comes from the ammo that is most available in the US. As with all ammo, there are varying levels of power and reliability.

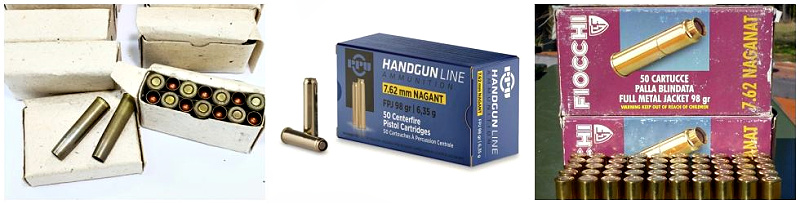

Fortunately, there are some better-quality commercial cartridges out there.

The Prvi PPU is cheap but decent. You know what you’re getting from them and Fiocchi makes pretty good stuff. Both of those loads feature the crimped brass and undersized bullets loaded at 98 grains. Not as powerful, but probably the most reliable commercial cartridges. The crimped brass does have one advantage over the military loads: it’s easier to extract the spent casings. The military stuff, probably because of the better seal, can get pretty sticky.

For a long time, the majority of available ammo was underpowered.

They were pleasant target loads meant for the range. They were clearly not powerful enough for defense. The early boxes of cartridges I bought for my son’s Nagant were like that. Much of this commercial stuff was also rather poor quality. Looking at you, Red Army Standard.

Low power and less than high quality is a bad combination and the Nagant’s reputation has suffered in response. The crimped commercial ammo also reportedly uses bullets that are just a touch smaller in diameter to facilitate the crimping on the front end of the cartridge. This technique is supposedly easier and less expensive than the tapering of the military rounds but comes at the price of a less efficient seal. These cheaper rounds are not especially accurate. That’s the nature of cheap ammo.

Finally, no matter the quality of the ammo, the Nagant M1895 is all but impossible to fire accurately in the double-action mode. The trigger is just too heavy. I think that fact contributed to the myth of inaccuracy. Try it in single action. You’ll do a lot better.

Okay, if you’ve made it this far, you most likely understand why the Nagant Revolver can be suppressed.

The unique gas seal created by the moving cylinder allows the suppressor to function as designed, unlike revolvers which expel gas and energy through the cylinder gap. It requires a little work, but it can be done and, as noted earlier, the results are pretty amazing. The Nagant barrels are obviously not threaded so you’ll have to get that done yourself. The examples I looked at all required an adapter. Maybe some don’t but I didn’t see them. Depending on how you go about it, you may have to remove the front blade sight, which will require some machine work since the sight base is milled into the barrel.

Either way, whether you suppress it or not, the Nagant M1895 Revolver is a cool little weapon that doesn’t deserve the bad things that have been said about it. If you look at it through the lens of its time, it’s a well-made and fully functional firearm. And it’s different enough to remain cool over 125 years later.