Military Calibers: A Historical Overview of Military Ammo

William Lawson

Caliber choice goes hand-in-hand with military firearm advancement. From the early arquebus, military calibers were influenced by the weapons from which they were fired, the mission for which those weapons were designed, and the manufacturing capabilities of the day. Sometimes the caliber, and later the cartridge, drove the development of the weapon itself, instead of the other way around.

Tactics, logistics, and operational considerations also drive caliber and cartridge choices.

Questions like whether combat is expected in close-quarters urban environments play a role, as well as how much ammo an individual soldier can carry, or even how much space is available on ships or aircraft. Even the earliest projectiles were designed to fit the tactics of the day.

However, effective militaries plan for the future, meaning they leverage new technology to hopefully give themselves an edge in future conflicts. Let’s look at how those factors evolved, beginning with the 18th century, shortly after muskets decisively drove pikes from the battlefield.

Early Military Calibers (1700s-1800s)

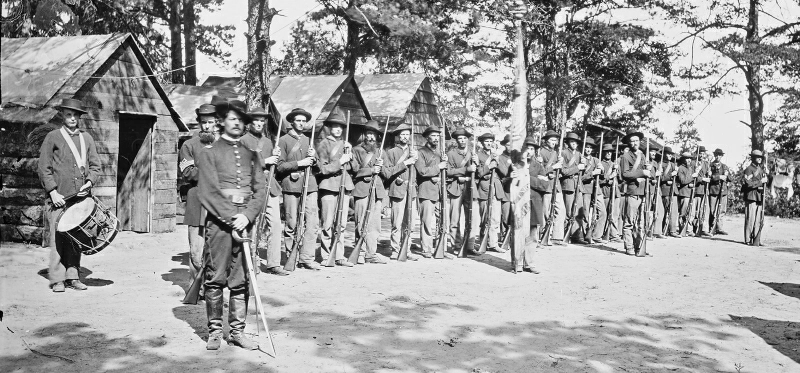

Modern readers and movie-goers often wonder why musket-equipped armies stood in tightly packed firing lines to shoot at one another. Comparatively primitive communications were a big reason, but weapons technology – including ammunition – also played a major role.

Smoothbore muskets weren’t very accurate, and their effective range was only about 50 yards. Even their extended range didn’t really go past 200 yards. Those muskets fired round shot, which isn’t the most aerodynamic projectile, creating significant drag, especially since it lacked a consistent spin.

The round projectile’s inaccuracy led to the prevalence of “buck and ball,” which combined a large .69 or .75-caliber ball with two smaller buckshot pellets. The shotgun-like effect produced more hits than a single projectile.

Mid-to-late 18th-century muskets were usually .69 or .75 caliber, with the latter most prevalent in the famous British Land Pattern Musket, better known as the “Brown Bess.”

The Brown Bess, in various forms, was the standard British Army musket throughout the 1700s and wasn’t officially replaced until 1853. Despite its .75-ish caliber bore (standardized production did not yet exist), the Brown Bess fired a smaller ball, .67 to .73-caliber, to account for the prodigious black powder residue that built up in the barrel.

The .67-caliber ball in a .73 to .79-caliber barrel made the Brown Bess notoriously inaccurate. The lack of a front sight made it worse. It’s no wonder that buck and ball became the preferred load.

.69-caliber muskets had the same problems, though they usually fired a similar .67 or .68-caliber ball like the Brown Bess. The smaller bore didn’t help much, given the round shot’s innate disadvantages. The Brown Bess is the most prominent example, but all smoothbore muskets operated on the same principle regarding ammunition.

Even Revolutionary-Era rifles, like the famous Pennsylvania and Kentucky Rifles, used round projectiles wrapped in a greased patch. Their rifled barrels did impart some spin by engaging the patch, making them more accurate and providing longer range. But rifling was a difficult process and very expensive. Most people couldn’t afford them, and craftsmen couldn’t turn them out quickly anyway.

The Baker Rifle, the British Army’s first standard rifle, was introduced in 1800 after the success of American rifles during the Revolution. But it still fired a round ball and was expensive to produce, only being issued to special rifle units.

Rifled muskets only became standard issue in the mid-1850s after the 1849 introduction of the “Minié Ball.”

The Minié Ball was a conical bullet with two to four grooves in its base. The grooves caused the soft lead to expand when the bullet was fired, engaging the barrel’s rifling to create a strong seal. The seal allowed greater compression, leading to higher velocities. The velocity combined with the spin imparted by the rifling to make a longer-range, more accurate projectile which delivered more energy upon contact.

Rifling techniques had evolved and were more economical with the onset of mass production, completing the progression of viable rifled muskets on the battlefield.

The Minié Ball was named for French Captain Claude Minié, who built on the earlier work of fellow Frenchman Henri-Gustave Delvigne, Captain John Norton, and gunsmith William Greener of England. Rifles equipped with the new round proved devastating to smoothbore-equipped Russian troops in the 1853-1855 Crimean War.

The Minié Ball allowed an effective range of 300 yards, with an extended range of hundreds more, depending on the rifle. No longer could enemy artillerymen set up just outside of musket range and rake vulnerable infantry with grapeshot or canister with impunity. Accurate rifle fire quickly ended that practice.

The Minié Ball also did more damage, shattering bones and shredding tissue far more effectively than musket balls. A London newspaper noted that the new round cut down the Russian soldiers “like the hand of the Destroying Angel.”

The Minié Ball’s performance was not lost on American observers, who returned with samples. James Burton, an armorer at the United States Arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, improved the Minié Ball in 1855, hollowing out the projectile and standardizing it for the new .58-caliber Model 1855 rifled musket. The new round was easily mass-produced, making it widely available for the looming American Civil War.

Claude Minié’s name is pronounced Min-YAY, but American soldiers called the new round the “Minnie Ball.” Its range and accuracy rendered the Napoleonic infantry charge obsolete, though Civil War commanders never fully learned the lesson, resulting in horrendous casualties in actions like Pickett’s Charge and Cold Harbor.

The Industrial Revolution and Caliber Standardization (Late 1800s-World War I)

The manufacturing boom precipitated by the Civil War increased and improved mass production capabilities just as the Industrial Revolution spread from Europe to the United States. But early metallic cartridges had been in the works since 1851, and Benjamin Tyler Henry chambered his famous 1860 lever action rifle in a .44 caliber rimfire that saw limited Civil War service. The US government adopted the .44-caliber Smith & Wesson American as its first metallic cartridge-firing revolver in 1870. The centerfire .44-40 Winchester soon followed with the advent of the Winchester Model 1873.

Early metallic cartridge designs were essentially elongated percussion caps, as were used on Civil War-era muskets. Combining those new cartridges with new breechloading rifle designs finally ended the muzzleloader’s usefulness as a military weapon.

Metallic cartridges produced by modern manufacturing techniques allowed for the standardization of military calibers. Those processes led to the mass production of military firearms and ammunition. Black powder gave way to the far more efficient smokeless powder in the 1890s and early 1900s, creating the first modern military cartridges.

Five of the most successful cartridges from that time stand out: the German 8mm Mauser, the .303 British, the Russian 7.62x54R, and the American .30-40 Krag and .30-06 Springfield. The 8mm “Mauser” was actually developed by the German military’s Spandau Arsenal in 1888. But the 7.92x57mm round saw its greatest success in the famous Mauser Model 1898, which its designer, Paul Mauser, had chambered for the official German Army caliber.

The .303 British was also adopted in 1888, and like the 8mm Mauser, successfully transitioned from black powder to smokeless powder in the early 1890s. The .303 was first used in the Lee-Metford rifle in 1888 but became synonymous with the Short Magazine Lee Enfield (SMLE), introduced in 1903, which served British and Commonwealth forces into the 1950s.

Russia also adopted a new smokeless powder round for its Mosin Nagant M1891 rifle at about the same time. The 7.62x54R cartridge delivered similar performance to the new German and British rounds, and it featured a rimmed case, as did the .303 British. That’s what the “R” stands for. A rimmed case is designed so that the bolt face and extractor can more easily control the cartridge, though more modern rounds have long dispensed with that feature. Russia’s insular nature meant the 7.62x54R never caught on in the West until surplus Mosin-Nagants became available after the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union. However, it was ubiquitous throughout the old Soviet sphere of influence and is still used by the Russian military today.

The United States military’s first modern rifle cartridge was the .30-40 Krag, which was issued in 1894 in the Krag-Jorgensen infantry rifle. The .30-40 Krag used smokeless powder and was the standard US Army round until superseded by the .30-03 Springfield just nine years later. It served in the Spanish American War, but its performance didn’t match that of the European service calibers, which became evident when facing the 7mm Mauser-equipped Spanish troops. The superb 7x57mm Mauser was Germany’s export cartridge for Mauser rifles sold to foreign governments. Efforts to upgrade the .30-40 Krag were unsuccessful, leading to what eventually became the .30-06 Springfield.

The Krag was initially replaced by the .30-03 in 1903. But extended tests revealed weaknesses, resulting in a 1906 upgrade to the new .30-06. The .30-06 became the standard US military rifle cartridge, being chambered in such classic rifles as the M-1903 Springfield, the M-1917 Enfield, and the M-1 Garand.

Like the European nations, the US also used its infantry rifle cartridges for light and medium machine guns. The .30-06 served through the Korean War before being replaced by the 7.62×51 NATO cartridge in 1957 with the M-14 rifle.

The two Mauser cartridges, the .303 British, the 7.62x54R, and the .30-06 are still widely used today by hunters and military surplus enthusiasts. The .30-40 Krag is still available but has been relegated to a niche cartridge.

Two prominent military pistol cartridges also emerged in the wake of the bolt action infantry rifle revolution. German gun designer Georg Luger introduced the 9mm Parabellum, or 9mm Luger, in 1901. The cartridge was developed from Luger’s earlier 7.65 Parabellum round at the behest of the German military. The 7.65 Parabellum was used by European police agencies into the 1960s, but the 9x19mm cartridge served the Germans in both World Wars in pistols and submachine guns. It has since become the most successful centerfire handgun cartridge in history and is popular in submachine guns and carbines.

While 9mm emerged in Europe, the United States took a different approach. The US Army had long depended on .45 caliber pistol cartridges before going to the lighter .38 Colt in 1892. The Spanish-American War and subsequent Philippine Insurrection showed the .38 Colt’s anemic qualities, prompting a quick return to the more powerful .45 Colt, albeit in now obsolete revolvers.

Colt and John Moses Browning responded with the Colt M-1911 semi-automatic pistol chambered in .45 ACP. Both the firearm and the cartridge were successful immediately.

The .45 ACP went to France for World War I in the 1911, as well as the Colt and Smith & Wesson M-1917 revolvers, which helped address the shortfall of 1911 pistols. The World War II-era M-1A1 Thompson submachine gun and the M-3 Grease Gun were also chambered for Browning’s cartridge.

The .45 ACP-chambered 1911 was the US military’s standard pistol until the 1985 adoption of the 9mm Parabellum-chambered Beretta M-9 pistol brought the US into line with the NATO standard 9mm chambering.

World War II Caliber Revelations

The belligerent nations entered World War II with full-size battle rifles chambered in the cartridges discussed previously, along with the Japanese 6.5mm and 7.7mm rounds, the Italian 6.5mm, and the French 7.5x54mm. But the combatants soon learned the value of smaller caliber, fully-automatic submachine guns on a battlefield that rarely required long-range fire by infantrymen.

The pistol caliber subguns, however, lacked the intermediate-range capability necessary for a standard infantry weapon. The Germans addressed the need for a best-of-both-worlds solution with the MP-43 and MP-44 Sturmgewehr, the world’s first true assault rifle. The gun fired a 7.92×33 cartridge which had been cut down from the standard 8mm Mauser. The new rifle, coupled with the intermediate-size rifle cartridge, provided superior firepower while allowing soldiers to carry more ammunition.

The Soviets took a similar tack late in the war with their intermediate 7.62x39mm cartridge, which first appeared in the SKS rifle. The Kalashnikov AK-47 rifle soon superseded the SKS, and the Soviets went all-in on the 7.62×39 round. That decision gave them a decided early small arms advantage in the emerging Cold War, with the select-fire AK-47 becoming the standard infantry rifle while the United States still relied on the .30-06 M-1 Garand and the British were using bolt action .303 Enfields.

The Cold War and NATO vs. Warsaw Pact Standardization (1950s-1980s)

NATO and the Warsaw Pact standardized their military calibers over the next four decades. The Communist Bloc nations did this more easily thanks to Soviet domination. The 7.62×39 cartridge became ubiquitous across all communist countries and was exported to sympathetic regimes and anti-colonial revolutionaries throughout the world, along with the AK rifles from which to fire it.

The 7.62x54R remained in Eastern Bloc sniper rifles and machine guns, while the 9mm Makarov became the standard pistol caliber in 1953. The Makarov round’s 9x18mm dimensions were reportedly developed to make sure enemy combatants could not use captured Soviet ammunition in their own 9mm Parabellum firearms. Its performance falls short of the NATO 9mm round, but is a bit better than the .380 ACP, which it resembles. The Czech CZ-82 and Polish P-64 pistols were chambered in 9x18mm, as well as the Makarov pistol itself.

NATO, influenced by the United States, chose a different path to a standard rifle caliber. The US lagged behind on the intermediate cartridge front, insisting on a full-size .30 caliber battle rifle to succeed the aging Garand. The only concession to making a smaller cartridge was reducing the venerable .30-06’s case size to create the 7.62×51 NATO round, which is very close to the .308 Winchester.

The round was developed for the Garand-inspired M-14, a select-fire battle rifle that was obsolete when the Army adopted it in 1957. The US forced the new cartridge onto its NATO allies as the new standard, despite the Europeans’ desire for a smaller cartridge such as the promising .280-caliber cartridge developed by either Enfield or FN (there’s some dispute over the round’s origin).

The US had skated by the intermediate cartridge trend by leaning heavily on the M-1 and M-2 Carbines used in World War II and Korea. Those rifles served well but had originally been intended to replace the 1911 pistol with service troops. The .30 Carbine cartridge was basically a glorified pistol round and its performance fell far short of the Soviet 7.62×39.

The M-14 failed spectacularly in Vietnam, being uncontrollable in automatic fire and clearly inferior to the 7.62×39-chambered AKM pattern rifles against which it was pitted. The lone NATO bright spot of this era was the Belgian FN FAL rifle chambered in 7.62×51 NATO. The rifle performed admirably and became known as “the Right Arm of the Free World.” But the AK was still better, not least because of its cartridge.

The M-14 debacle finally forced the US Army to concede its position on the battle rifle concept. The new M-16 was rushed to Vietnam, along with its new 5.56x45mm NATO cartridge, which was based on the .223 Remington.

The M-16 story, and that of its cartridge, are tales unto themselves, and a sorry testament to the power and intransigence of an entrenched military bureaucracy. But by 1969, with the introduction of the M-16A1, US forces had a weapon and a cartridge that measured up to the Soviet 7.62×39. They were just 20 years late. NATO formally adopted the 5.56×45 as its standard cartridge in 1980. Again, decades late.

5.56 NATO vs Russian 7.62x39

The 5.56 NATO, in several forms, and 7.62×39 cartridges have faced off on countless battlefields since 1962. Is one better than the other? Let’s take a look. Here are a few specs:

5.56 NATO | 7.62x39 | |

|---|---|---|

Bullet Diameter | 0.224 inches | 0.312 inches |

Neck Diameter | 0.253 inches | 0.339 inches |

Base Diameter | 0.377 inches | 0.447 inches |

Case Length | 1.76 inches | 1.524 inches |

Cartridge Length | 2.26 inches | 2.205 inches |

Powder Capacity | 28.5 grains H20 | 35.6 grains H20 |

Maximum PSI | 55,114 | 45,010 |

The 5.56 NATO is smaller and lighter, if a bit longer. The 7.62×39’s 30-caliber bullet makes a bigger hole. The Russian round also has more energy at the muzzle, with roughly 1,500 ft-lbs. to the 5.56’s 1,275.

The 5.56 cartridge’s shoulder design and higher pressure rating give it a muzzle velocity in the neighborhood of 2,900-3,200 feet-per-second. The 7.62×39’s muzzle velocity is a much slower 2,300-2,500 fps. The greater velocity gives the 5.56 NATO a longer range.

A standard 123-grain 7.62×39 bullet drops about 44 inches at 400 yards, while the average 62-grain 5.56 NATO bullet drops about 24 inches.

The 5.56 NATO has also shown more ability to evolve, while the 7.62×39 is essentially the same round that it was in the 1950s. Both cartridges are being superseded by their respective militaries, though both are still quite capable and remain in service.

The 5.56×45’s emergence led the ever-paranoid Soviets to expand their rifle cartridge options in the early 1970s. Worried that the smaller, faster 5.56 might represent some hidden advantage to their tried-and-true 7.62×39, the Soviets developed the 5.45×39 cartridge for their AK-74 series of rifles. Similar ballistically to the 5.56, the 5.45×39 gave the Soviets a lighter round with a longer range. It remains the standard Russian military rifle caliber today.

Modern Advancements and Experimental Military Calibers

The US Army is now fielding a new 6.8mm (.277-caliber) round designed to eventually supersede the 5.56 NATO. This program has been in motion for over two decades.

Experiences in Afghanistan demonstrated the need for a squad-level weapon capable of effective fire out to 500 meters and beyond. Enemy combatants increasingly set up outside of effective 5.56 range and sniped with higher caliber, longer-range rifles.

Some American units addressed that situation by adding a few 7.62 NATO-chambered AR rifles to their patrol loadouts. The idea was to make the ambushers believe the Americans only had M-4s, then answering with effective 7.62 fire. The Afghans called those 7.62 rifles “the Barking Dog.” I was fortunate to purchase one of those rifles a few years ago, and it is indeed effective. But those were expedient outliers used mostly by special ops units.

The Army wants to give every combat unit the same capability. But rather than go back to the 7.62 NATO, the 6.8 round is being phased in to provide that longer range, while also, hopefully, retaining the advantages of a lighter cartridge in a closer, perhaps urban, environment. The 6.8 is quite capable of effective fire at range while being lighter than the 7.62. The 6.8 has also been developed with armor-piercing capabilities to defeat all current and planned armor systems.

The question remains as to its efficacy at short to intermediate range where the 5.56 excels. The 6.8 is heavier than the 5.56 and the larger case reduces capacity compared to what soldiers carry now. The 6.8 is an “in-between” round that seeks to be as versatile as possible. One wonders whether the Army strayed too far from the battle rifle concept in the wake of the M-14’s failure. Remember, the FAL in .280 (right there with the 6.8’s .277 caliber) was considered, but politicians demanded an American-made rifle.

The Army has gone all-in on the new round, and the “Next Generation Squad Weapon” is and will be chambered for it, as will squad-level machine guns. But the transition will take time. Army planners note that 5.56 and 7.62-chambered weapons will remain in the Army’s inventory for the foreseeable future.

The US military, and by extension, NATO, is moving toward more versatile cartridges like the 6.8. The Global War on Terror revealed some gaps in the US arsenal’s capability, but the specter of peer-level conflict remains with Russia and China seeming ever more belligerent.

Russia still relies on its Cold War cartridges, which are admittedly effective. The US could do the same, but the 7.62 and 5.56 NATO cartridges are so far apart that logistics could become a problem in a fluid mass deployment situation. A reasonable do-it-all cartridge, if such a thing exists, could ease that concern.

The Future

Whether the 6.8 can fully replace the 5.56 remains to be seen, but the search for that sweet spot round isn’t new. Perhaps the earliest attempt to create what we might think of as an “assault rifle” used the Japanese 6.5mm round, which had good range, comparatively lower recoil, effective terminal ballistics, and was lightweight compared to the battle rifle cartridges of the day. That weapon was the Russian Federov Avtomat and the year was 1915. Designer Vladimir Federov might just be smiling somewhere.

Another recent cartridge with military applications is the .300 Blackout. The Army wanted a new cartridge optimized for close-quarters work, preferably suppressed, in the M4 carbine. The new capability was meant to ease logistical concerns by enabling the M4 to replace the 9mm MP5SD submachine gun. Soldiers could just use the ubiquitous M4, while using new, better-performing ammo. The result was the .300 Blackout cartridge, developed jointly by Advanced Armament Corporation and Remington. The .300 Blackout is still a specialized military round and only used by certain units at this time.