Home / Silencer & Gun News / Interview with Jonathon Shults

Interview with Jonathon Shults

Home / Silencer & Gun News / Interview with Jonathon Shults

Interview with Jonathon Shults

Barbara Baird

Some may think of Jonathon Shults, founder and president of SilencerCo, as a quiet genius. He’s that guy from Utah who started as a recording studio engineer and a professional bassist, who now runs the world’s largest suppressor company. He’s the author of an American dream success story, where he and his business partner, Josh Waldron, started making a suppressor in a garage back in 2008. Today, the company continues to flex and evolve as it evokes changes in the firearms industry. You may be able to tell why, when you read the following transcript of the interview I recently conducted with Jonathon.

Barb: There’s not a lot about you out in the world. Why is that?

Jonathon: I stayed quiet for a long time. Josh was pretty loud, so I stayed quiet. … But I think some clarity in the world is a good idea.

Barb: If people ask you, “Hey, Jonathon. What do you do?” (elevator speech)

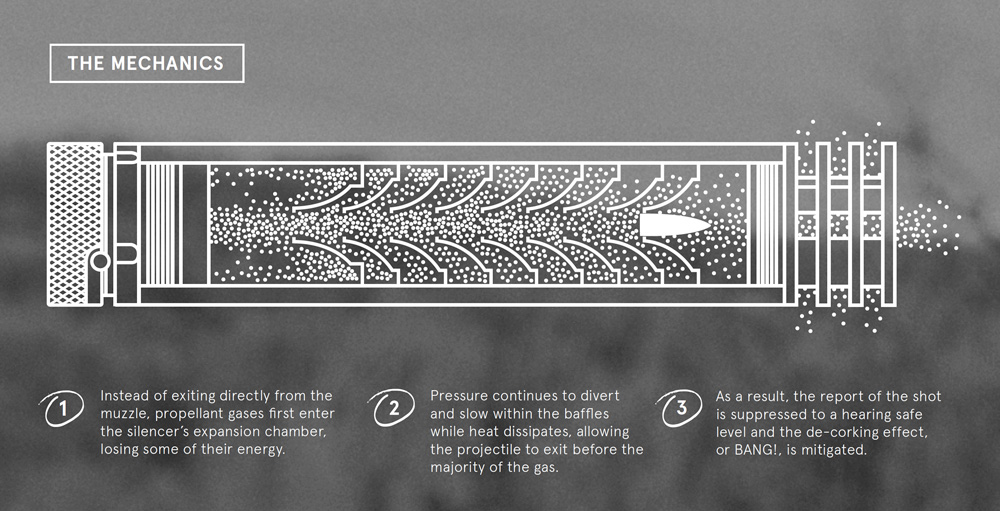

Jonathon: Normally, I avoid it. Sometimes, it’s kind of confrontational. Mostly I’m an adventurer, and an engineer. I love the mechanics of all things. I love to explore and that’s what started the company – looking at how to make silencers — and I love the mechanics of that and I love the mechanics of guns. As we built this company, I discovered that I loved the mechanics of management and organization. I’m an inventor, but I’m also a creator and an organizer.

Barb: I’ve heard that you see potential in people that others might not see …

Jonathon: Early on, I had a saying, “You learn how to do something, I’ll pay you for it. I don’t care if you went to school and I don’t care if you learned it here.” One of our models is “People, Passion, Precision.” The reason that “people” is on top, is because I hope that anyone that enters this building or is associated with this company leaves better than when they arrived.

One example, one of my engineers – I played hockey with him. I gave him a tour of the facility and I saw his eyes light up when he saw the machine tools. It turns out his grandpa was a machinist. We hired him and he started learning how to machine. He was a tinkerer and he liked to make model airplane parts. I told him he could make anything he wants in his off-time. Eventually, he became an engineer and he’s one of our lead engineers and he invented the Maxim 9 and the Salvo 12, and many other projects. And, he’s still with us.

Barb: What did you do in your childhood that made you what you are today?

Jonathon: My parents are both musicians and free thinkers. My mother instilled a blind confidence in me, I just believe that I can do anything. I’ve been an adventurer since I was a little kid.

Barb: What did you invent as a kid?

Jonathon: A lot of traps [laughs]. You know – the banana peel that opens when you open the door and drops an egg on your mom’s head. We were always making huts and underground things. My grandma bought me this little robot for my birthday. Back then, they didn’t do a lot, right, they just went forward until they ran into something and then, back up and turn.

So I took it apart. I got in trouble. Then, I wanted another one – that smoked. I got it and I’m not sure I even played with it before I took it apart. I was instructed, “Do not take this apart!” And I remember thinking, “Why? It’s my toy and I like to see what’s inside more than I want to use it how it is!” Early on, my mom’s friends would bring over their broken radios and TVs and I would fix them. Never very well, but they would work when I was done! I’ve just always been this way.

Barb: When did you learn how to play an instrument?

Jonathon: I learned how to play guitar when I was 14. My dad taught me how to play a bunch of folk songs and finger-picking stuff and I got introduced to the bass guitar when I was 15. Music taught me how my brain works. I was a hyper-focuser; I really stunk at school. I was lucky to graduate. When I had something I was passionate about, I could study it so intently that I could become good at it. That was my career path before SilencerCo.

Barb: What did you do before SilencerCo?

Jonathon: I became a professional bassist and I would do recording sessions for other musicians and other bands. I played in bands and taught music and worked in a music store. In 2000, I created my first recording studio, and I decided I liked that path better than going on tour, because it would be a better family life. From there, I decided I needed to make a website, so I learned how to program websites. I realized the artists I was doing music with needed websites. So I started learning how to do data-base driven, back-end stuff.

Right before SilencerCo, I was running the recording studio full-time and had a part-time gig doing software stuff on the back. Josh and I tried to create another company with that technology that I had created. SilencerCo was supposed to be just a hobby. SilencerCo took off and the other one totally flopped. We didn’t expect it to be what it is today. We were just doing it out of a garage at first. Then, we ended up in a 2800-square foot building with one machine in there, and that’s where we started – with the Sparrow.

Barb: Let’s talk about the names of some of the silencers.

Jonathon: I don’t know why we started with birds. I remember that we picked “Sparrow” and then, we kind of stuck to birds. I think it was an accident.

Barb: Let’s talk about the Harvester.

Jonathon: The Harvester is a pivotal point in the business. Prior to the Harvester, I was a new shooter, a baby shooter. The whole industry at that time said you need the most durable cans; they need to be full-auto rated – essentially military stuff. One day, my friends took me hunting prairie dogs, so I took my AR-15 with green-tipped bullets. Green tips suck and having a big, heavy military can on the end your gun really stinks.

Through that process, I realized, “I don’t like this.” We needed to make something that’s light and doesn’t need to be full-auto rated. It just needs to be able to hit something. That birthed the Harvester. We started hunting a couple of times a week, developing that product. Then, we got into the bigger calibers. Back here we hunt a lot of elk. I wanted something that was affordable and light and served the purpose. From the beginning, it was designed as a hunting can.

Barb: Have you evolved as a hunter?

Jonathon: Yeah, I went into a big surge. We did the Alaskan bear hunts, bigger elk and deer, Colorado deer, Texas hunts and hog hunts. Now, I don’t hunt as much. I really learned a lot about it. Some of our other products came from that, too. The Omega came from the Harvester class.

Barb: What is the story of the Omega?

Jonathon: What happened is that some of our original investors left, sold their shares and created a new company. That new company, out of the blue, launched a product and we wanted to combat that product and beat them to shipping. They’d already launched it. For the past two years prior to that, we had a product called Harvester Match. I’d been shooting it at PRS matches, hunting and everything. Back then, the team didn’t want to launch that product, and it didn’t make sense to them. Who needs another light, short can?

This was my opportunity, so during one of my staff meetings, we talked about that company and I said, “I have an idea. I’m not sure the world will love it. I love it. … If I change these three things about my design, it would be very robust, it would meet lots of full-auto requirements, [but] wouldn’t be as indestructible as the Saker line.” Then, they came up with the name “Omega,” and I think it was a little bit of a power play against the competitors.

Barb: Isn’t Omega the top selling suppressor?

Jonathon: It’s ironic, its intent was never to become what it became. Its intent was to be, well … we figured it would be OK. We figured it would be like the Harvester, like the big dogs, but not important. From the day it first shipped, it outsold everything that we’d ever made – by a long shot. Kinda cool.

Barb: The Sparrow is super popular too, right?

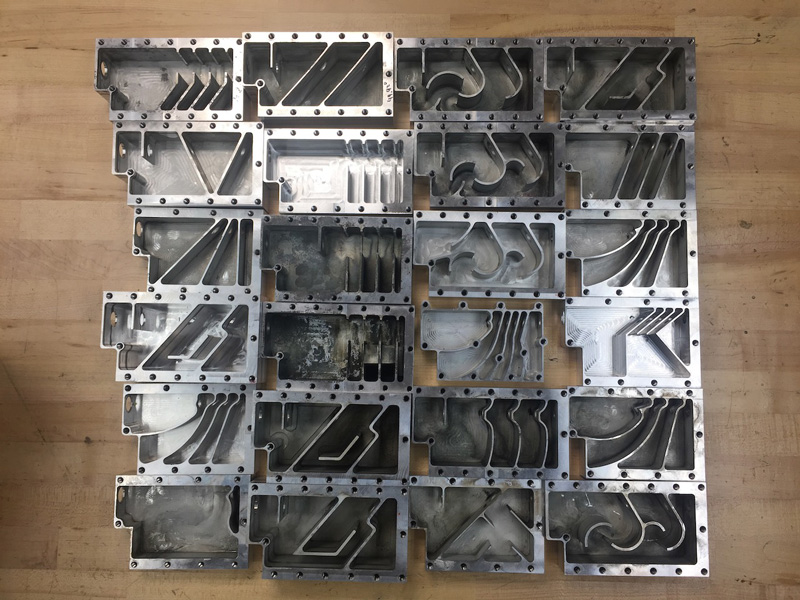

Jonathon: The original business plan was to make a simple .22 can. Let’s just make something simple, cheap to develop, get some manufacturing under our belt. I had to learn how to run a simple CNC machine. Mike Pappas, an early partner who had once worked at a gun store, came up with the idea of the half-pipes that are in the .22 can. He designed them on a cocktail napkin, and I engineered around that. We didn’t realize that the design would be unique enough that it made it special (the Sparrow).

We ended up patenting it right off the bat. The first one did OK. It sold less than 100 units a month for the year we had it, then, we launched the Osprey. One day I woke up and thought, “I think I know how to make the best .22 can ever. Would it be the quietest? I don’t know, but it would be the most rounded.” That’s when the current one [Sparrow 22] was made, and it’s harder to make, but its feature sets were far better. It sold hundreds a month since the day it launched, and it’s actually selling more than the day it launched.

Barb: You’ve gone from hockey to shooting to dirt bikes. I heard you’re almost semi-pro on a dirt bike. What do you like about dirt biking?

Jonathon: Dirt biking checks all the hobby boxes for me. I’m a very methodical person and I love mechanical things. I also love sports. In sports, you have the athleticism and the technique. Dirt bikes have all that, and it’s a family sport. My wife has done it a few times, but it’s mostly me and the four kids. My wife, Tiffiny, will mostly go exploring – maybe rock hounding – so if the kids don’t want to do dirt biking, they’ll go hiking with her. Dirt biking checks a few more boxes than shooting did for me.

When I was getting back into shape, I was running a lot. I bought a Garmin watch and one of my engineers got a Garmin watch and we followed each other. He had just bought a dirt bike and he went on a Saturday ride. I looked at it and it said he averaged like 176 beats per minute for 2-1/2 hours. So, I called his bluff. I called him and I said, “You’re sitting on a motorized vehicle. There’s no way you had your heart rate for that high for that long!”

One of the machinists was a motocrosser. They pointed out that motocross is considered the most athletic activity other than soccer. I tried it. I remember, the second ride I went on, I didn’t make it up a sand hill and I was pushing my bike up and I got to the top and about passed out. One of my employees said, “Pretty athletic, huh? Pretty physical?” Some of my first races, in desert racing, I’d average 165 to 175 beats-per-minute for four hours solid. It’s pretty intense. Then, there’s the adrenalin piece of it.

Hockey does this, too. When you play a sport, you’ll work harder than you think you are, and you won’t know until you stop and then, you’ll need to puke. Dirt bike does this, too. Mentally – and hockey doesn’t even do this – when you ride for four hours, you cannot think about anything but riding. That’s very therapeutic for someone like me, who thinks too much.

Barb: So, you’ll be dirt biking for a while?

Jonathon: Yeah, I don’t see that coming to an end.

Barb: How old are your kids?

Jonathon: Girl, boy, girl, boy, about 2 years apart, from 15. One’s learning to drive now.

Barb: What do you see in the future for suppressors?

Jonathon: Since we started, gun companies weren’t supporting suppressors. Threaded barrels were difficult to find. In fact, most threaded barrels were done by gunsmiths. What’s cool to see, is that most guns can come with a threaded barrel. The biggest thing in the silencer world would be the ATF approving stuff faster. If we could get the forms to have a shall-issue, like with concealed carry permits, that would really change the world of suppressors.

Technology wise, I think you’re going to see more guns support silencers in a better way – particularly in semi-autos – where you’re going to see them start designing guns around being suppressed instead of us designing suppressors around guns.

Of course, we have secrets in our pockets … but, that’s secret sauce.

What’s fun about silencers is that this industry is still small. I think less than 10% of FFLs have SOTs [The SOT, Special (Occupational) Tax, in this case is paid by a firearms dealer to the ATF in order to legally sell suppressors]. To me, that’s a good indication of potential for growth.

Barb: Do you think that if the Hearing Protection Act passes, you’ll have competition from people making their own cans?

Jonathon: My job is to adapt to whatever environment we’re in. It’s my job to be prepared to adapt, and to be the strongest company we can be, no matter what the environment. It’s a philosophy that I’ve had since the music industry days where I did a service that lots of people could do.

I’m not sure I was better than the other guy. … Say I gave you all the information, every one of my patents and some of my trade secrets … say you worked right beside me and you learned everything. It is still my job to be better than you. Maybe this comes from sports, but If I get beat, I get beat, and that competition is good. I don’t fear any of that, and it’s all fantastic.

We carry a similar philosophy to Apple, which may have stemmed from my music, artistic base: Offer something special, or better, and people who want that will find it. So whether suppressors are regulated or not, we will still be striving for the best. The consumer should say, “I want that.”

Barb: How are we going to reach all the new shooters coming to the market?

Jonathon: Education has been a massive part of SilencerCo. That’s really all it is. I think that the majority of new shooters – not necessarily silencer buyers – have always purchased out of fear. I appreciate this fear more than previous types, because people are purchasing out of the true meaning of the Second Amendment. That’s really powerful. It also changes the way people look at guns. That piece is so important. My team is out at events. People touch [silencers], people shoot them, people experience them – they’re sold. From that point forward, it represents an experience.

Now, people know what silencers are … and that’s been massive. Education. That’s the key. For most of that education, you can do social media, but feet on the ground is always the best.

Barb: What if someone came in tomorrow and offered you a ton of money for SilencerCo, would you take it?

Jonathon: SilencerCo is my baby. The team that’s here in this building is awesome, and it took 11 years to make. Until I’m not allowed to be here, I’ll be here.

Barb: Anything else?

Jonathon: Our mission is just the truth. We do the things that we say we’re going to do. The times of a handshake in my world are real. Through business, we’ve tried to always be good at that … my partners weren’t always good at it. The natural man comes into play, often when you see money. We want to be who we say we are, and we want to be strong, honest, bold.